- ≡ Mnium palustre Hedw., Sp. Musc. Frond. 188 (1801)

- = Aulacomnium stolonaceum Müll.Hal. in Müller & Brotherus, Abh. Naturwiss. Vereins Bremen 16: 503 (1900)

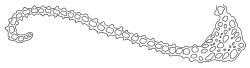

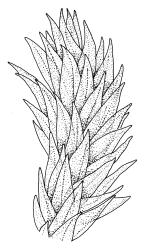

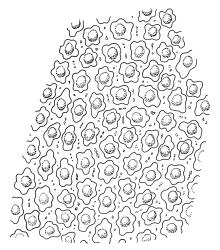

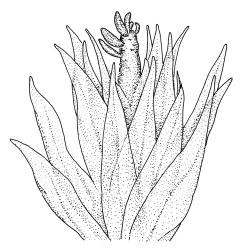

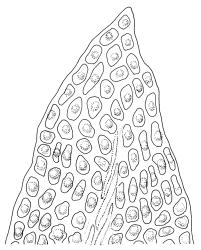

Plants medium to robust, yellow- or brown-green, forming dense turves. Stems erect, simple or sparsely branched (and reportedly branching by innovation), from c. 40 to >150 mm, occasionally terminated by gemmiferous pseudopodia, densely beset with red-brown, smooth rhizoids, in cross-section with a strong central strand. Leaves erect-spreading when moist, contorted and in well-defined spiral ranks when dry, oblong-lanceolate, broadly acute, obtuse or rounded, entire or serrulate near apex, oblong-lanceolate, slightly auriculate in alar angles, recurved on both margins nearly to apex, not or very weakly decurrent in N.Z. material, mostly 1.8–3.0 × 0.6–0.9 mm; laminal cells collenchymatous nearly throughout , irregular and ± stellate in outline, but mostly ± isodiametric, mostly 12–15 µm diam., but some ± elongate and larger, strongly once papillose-mammillate on both surfaces; basal cells pigmented and slightly enlarged in several (c. 6–10) rows, incrassate but not collenchymatous. Costa stout, c. 45–60 µm wide at mid leaf, sinuose above, failing several cells below apex, lustrous and projecting strongly abaxially in dry leaves, with elongate to linear cells exposed on both surfaces, in cross-section with a central layer of guide cells, two small groups of stereids, and larger abaxial and adaxial surface cells. Gemmae often borne on apical pseudopodia, brown, fusiform, composed of many (>100) cells, and c. 200–300 µm long.

Dioicous. Perichaetia terminal, subtended by innovative branches; perichaetial leaves somewhat more spreading but otherwise not differentiated. Perigonia and sporophytes not known in N.Z.

Crum & Anderson 1981, fig. 291; Crum 1994, fig. 406, d–i; Smith 2004, fig. 211, 1–6.

The sparsely branched, erect stems with dense light-brown tomentum, together with leaf shape, the lustrous, abaxially protruding costa and recurved leaf margins make this wetland species distinctive. The abaxially protruding costa and recurved vegetative leaf margins are more conspicuous when dry. Terminal gemmiferous pseudopodia are relatively uncommon in N.Z. material, but when present are highly diagnostic; the pseudopodia are variable in length but often c. 2–3 mm. Occasionally a few highly reduced and modified broadly ovate leaves occur on the pseudopodia below the apical cluster of fusiform gemmae. Under the microscope the collenchymatous and strongly mammillate laminal cells and sinuose nature of the costa provide further distinction. In dried herbarium specimens the gemmae are often fallen leaving the pseudopodia to appear naked. When well developed, A. palustre is unlikely to be confused with any other N.Z. species.

SI: Nelson, Marlborough (Molesworth, Branch River), Canterbury, Westland (near Ross), Otago, Southland; M.

Adventive. Australia*, Argentina*, North America*, Europe*, and Asia*. Reported from Mexico, Dominican Republic, and northern South America by Crum (1994) and from Tasmania by Dalton et al. 1991; see also Seppelt et al. 2013). Bell & Catcheside (2006) detailed its distribution in Australia and cited it from "southern South America" without further information.

Given the relatively large number of South I. collections (c. 50 in CHR) and the range of habitats this species occupies, the absence of confirmed records from high elevation localities on North I. is remarkable, and corroborates the hypothesis that this species is adventive in N.Z.

Occurring in a variety of montane to alpine wetlands, including cushion and Sphagnum cristatum-dominated bogs, tarn margins, flushes, Carex-dominated marshes, and Chionochloa rubra-dominated grassland. Often forming extensive turves square metres in extent. Occurring c. 500–1800 m. Often associated with Climacium dendroides and Sphagnum cristatum; less frequently associated with Breutelia pendula, Drepanocladus aduncus, Philonotis pyriformis, and Sanionia uncinatus. A J.K. Bartlett collection seen from "near Ross" in Westland L.D. suggests that it may occur at lower elevations than recorded above.

The first confirmed N.Z. specimens were collected at "Ben Lommond" [sic], near Lake Wakatipu in 1896/97 by H. Schauinsland and in the "Mt. Cook District" in 1907 by James Murray. These early collections were followed by a very few collections made in Marlborough and Otago in the 1940s. The apparent failure of earlier South I. collectors to gather what is now a relatively conspicuous species suggests this species is an introduction to the N.Z. flora. There is, for example, no material in the Beckett herbarium. While the mid to high elevation palustral plant communities commonly occupied by A. palustre do not immediately suggest adventive status, such sites have been formerly extensively grazed by both sheep and cattle. With its commonly-produced gemmae, this species seems a likely candidate for dispersal by either livestock or aquatic birds. Aulacomnium palustre is considered here to be an introduction to the N.Z. flora.

A less likely hypothesis is that A. palustre may have been a rare native species that expanded its range following grazing-induced modification of montane wetland plant communities. There are a number of striking similarities between the N.Z. distribution and collection history of A. palustre and those of Climacium dendroides.

B.H. Macmillan (pers. comm., 15 Aug. 2008) informed me that she collected A. palustre from containers of cultivated plants at the Christchurch Botanical Garden. She speculated that gemmae or plants may have been introduced to the Garden with Sphagnum used for horticultural plant propagation.

It is difficult to definitively state that a species is indigenous or adventive, and it is sometimes considered a precept of plant geography that the absence of collections does not indicate a plant species is absent from a given region. However, in the instance of A. palustre, which is now (2014) a very widespread and conspicuous component of the montane to alpine vegetation, the failure of discerning and widely travelled 19th century collectors (e.g. Beckett, Berggren, Brown, and others) to collect it provides strong, albeit circumstantial, evidence that this species was either absent or very rare in South I. montane wetlands at the time these collectors were active. Collectively, the capable late 19th to early 20th century South I. collectors were exceedingly unlikely to have failed to collect such a distinctive, [currently] widespread, and [currently] sometimes abundant species. The sudden burgeoning of A. palustre collections in the years since 1896 (and particularly since the 1940s) suggests introduction and subsequent rapid range expansion, although indigenous status (and analogous range expansion) cannot wholly be ruled out. The possibility of repeated introductions, possibly with horticultural materials from the northern hemisphere, also cannot be discounted. Neither Dixon (1926), Sainsbury (1955), Beever et al. (1992), nor Fife (1995) has previously questioned the indigenous status of A. palustre.

A synopsis of the current, very sparse, knowledge of this species in mainland Australia, Tasmania, and Macquarie I. is appropriate here. The oldest documented mainland Australian collections of A. palustre appear to be specimens (in herb. NSW) from the Australian Alps in N.S.W. and confirmed by G. Bell (pers. comm., 21 Aug. 2013). The collections were made in 1901 and 1904 by W. Forsyth and W.W. Watts, respectively. Bell & Catcheside (2006) reviewed the occurrence of A. palustre in mainland Australia, and recorded it from four localities "in open grassy swamps amid subalpine sclerophyll woodland" in N.S.W., Vic., and A.C.T.

The few published reports of this species from Tasmania are confusing. By far the oldest Tasmanian report is Wilson’s (1859, p. 192), based on a Gunn collection from "Formosa" near Campbell Town (L. Cave, pers. comm., 20 Aug. 2013). Bell & Catcheside were unable to locate the Gunn collection in any Australian herbarium, but is seems unlikely that Wilson (who noted the Gunn collection had the highly characteristic pseudopodia) would have incorrectly named such a distinctive plant. Bell & Catcheside also considered "the only recent [Tasmanian] specimen at HO [to be] misidentified". The genus Aulacomnium was accepted from Tasmania by both Dalton et al. (1991) and Seppelt et al. (2013) but they neither saw material nor provided significant further information. The status of this species in the Tasmanian flora thus remains unsettled and beyond the scope of this Flora.

The modern occurrence of A. palustre on Macquarie I. was documented by Seppelt (2004). Although Seppelt did not consider A. palustre adventive there, a reconsideration of its status there, seems warranted.